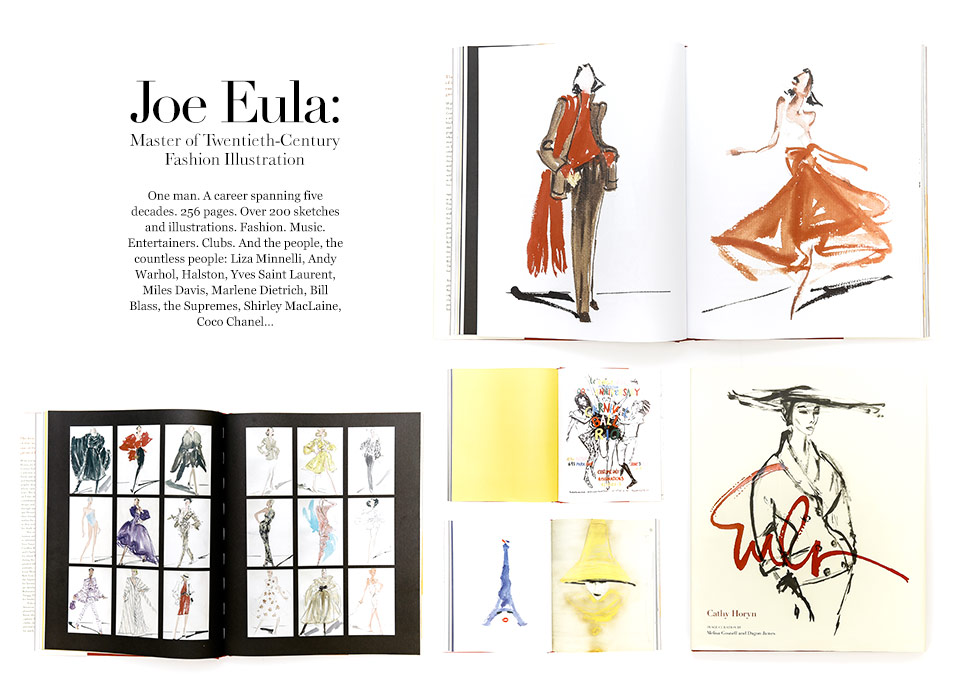

Fashion illustrator Joe Eula had an unbelievably rich and diverse career. He covered (and sketched) innumerable couture shows, created album covers and club posters, designed costumes, had his own line of china for Tiffany & Co., served as Creative Director of Halston during the Seventies… and then there’s the Bronze Star he received for his heroic efforts during the war. You can read about it all in Cathy Horyn’s new book, Joe Eula: Master of Twentieth-Century Fashion Illustration. Here, we chat with the former Fashion Critic for The New York Times about the artist, whom she initially met in the fall of 2001 when she interviewed him for Bare Blass, Bill Blass’ memoir. They stayed friends — and, coincidentally, were neighbors in Upstate New York — and would remain so till his death in 2004.

Melisa Gosnell, who’s in charge of Joe Eula’s images, and Harper Collins approached me. I said yes right away because I felt, one, I knew Joe and liked his personality so much and, two, it’s tough to do books about people because everything is known or often seems that way, but in Joe’s case, there was a lot I didn’t know. I knew it would be fresh territory for me. We signed the contract in the fall of 2012.

In your research, what surprised you that you didn’t know before?

A lot. Because all the times I sat there in his kitchen up in Hurley, New York — he’s making pasta and we’re sitting at this amazing butcher-block table, a fire to my left and the stove behind Joe, just yakking about story ideas and things that are going on in fashion — it never occurred to me to ask Joe what it was like to work for Halston. It’s not like I got the sense he was hiding something or didn’t want to talk about it. He just was very present tense.

Some examples of those surprising finds…

I thought the war years were amazing. His letters from that time — I love that he called his mom Fatty. He never talked about the fact that he was a legitimate war hero, so that was interesting. And every so often I’d be shocked to find photos of Joe walking into a party with Barbra Streisand. I didn’t know about that. And there are a lot of photographs of Joe with Lauren Bacall. She was a close friend of his in the late Sixties, early Seventies.

How would you describe his work?

There are good Joe Eula drawings, there are bad Joe Eula drawings — you can’t deny it. But he was unique in that he was able to get a sense of movement and spontaneity better than almost anybody. His illustrations felt like jazz, like something improvised. He’s hard to beat for that. We found this drawing in Town & Country, 1949 or 1950, of a Charles James cocktail dress — the simplicity of the line was perfect. It’s so modern. Liza [Minnelli] said — and this is important — that he got the intent of the dress. This goes back to Joe being a jack of all trades — he was able to design clothes, design sets… Joe visualized things in a very complete way. Instead of just drawing it, he got the sense of movement and the mood.

And his work vs. other famous fashion illustrators, like Eric, Gruau and Bouché?

[Illustrator] David Downton said that all those great illustrators of the pre- and postwar were working for Vogue, Harper’s Bazaar and the French fashion magazines. They had more time to execute the drawings. Joe was on newspaper deadlines — he started out doing magazines and advertising, but his name was made with Eugenia Sheppard and the New York Herald Tribune. It’s sort of an apples-oranges thing when you’re comparing him with the others.

Joe did a lot — club posters, costume designs, album covers… Did he consider himself a fashion illustrator who did other work on the side? Or an illustrator whose work included fashion?

I think he considered himself primarily a fashion illustrator. He had enormous longevity when you think about it. I mean, he started right after the war. I think he did other things because that had to do with the times. Warhol — a very different person, with very different talents and ambitions — started out doing illustrations. A lot of those guys did illustrations for department stores, advertising, record albums and things like that. But fashion illustration was really the bread and butter for Joe. By the time he gets to Italian Harper’s Bazaar, he’s making a lot of money with them. And then Halston…

Joe was Creative Director there…

Enrique Maza [Halston’s then-assistant] explained that Joe was really in the studio sketching. It was Joe who sat there on the floor, sketching the collection while it was in progress. They didn’t use Polaroids; they used drawings.

And Joe’s influence on Halston’s style?

I knew [designer] Fernando Sanchez pretty well — he was a great source for me on a piece I did on Saint Laurent, when the company was sold to Gucci — and he made the comment that Elsa Peretti and Joe Eula really contributed to Halston’s success. I was always curious about that.

Sanchez, China Machado, Liza Minnelli — they all comment on that in your book. But what do you think? Did Joe really help define Halston’s style?

I think that Joe was a catalyst. The outrageousness of Joe loosened up Halston and gave him more freedom to do things. I mean, Joe was really persuasive when you talked to him. He was also so much of a modernist and a real American guy — he liked simplicity, he liked dash, he liked that American thing. Joe lived and breathed it in a way that was really confident. But I do think that once Halston got going, he was more than capable. I think they had an influence, but I don’t take away anything from Halston. Once Halston is up and going, you can’t stop him.

Your favorite memory with Joe?

My first meeting with Joe at his apartment at the Osborne [for an interview for Bare Blass] — we bonded right away. I think a lot of people did that with Joe. What I thought was funny was that I walked into his kitchen and he just said, “Stand there.” I knew what he was doing [sketching me] and I just obeyed. There was a trust right away that I should do that. Once we became friends, I loved driving up to Hurley because my house is about an hour from his. There were a lot of good times up there. We had no agenda, we had no plan. We were never in a hurry.

The story ideas you tossed around sitting at that butcher-block table…

A feature on Belmont Park — we went the opening day and Joe did the watercolor illustrations. Walmart — there was a time, around 2001, when the fashion office was really hitting it. I would go up to Walmart and find these really cool things. Even Bill Blass — I had a cute little fleece top on once and he asked, “Is that Marc Jacobs?” “No, it’s Walmart!” So I told Joe and he said, “Let’s take you to Walmart and I’ll illustrate you there.” So we went to the Walmart in Kingston, New York.

That first drawing he did of you — it’s your Twitter photo now…

It’s one of my favorite prized possessions. Later on, I commissioned him to do two more drawings of me in Hurley — they were nice but not as good as that first drawing.

Why do you think?

There’s just something so spontaneous about it. The later ones look more finished somehow. I mean, the proportions are good and the hair looks good — and he made me look skinny, which I certainly appreciated — but they’re not as freehand. They’re not as enchanting to me, for sure. I like the fact that the first drawing is very abstract. Like I said in the text, no photographer has ever captured what he saw, and it’s what I see.

Thoughts on fashion illustration today, in a world dominated by photography? If it isn’t there to document like before…

It’s just one piece of a larger problem in fashion. The other day I was in someone’s apartment looking at some George Platt Lynes nudes, platinum prints, and those prints are so much better than what you would get digitally today. There is something missing now. Everything has to be done so quickly and there are all sorts of technical processes that make that possible, but you lose a lot of texture, you lose what Liza was saying about the intent. It also relates to things done by hand; we have less and less of the hand involved in things. And I don’t mean handwork as in hand-beading.

You mean…

I remember a conversation with Raffaele Ilardo, who’s the head tailor at Oscar de la Renta and, before that, was at Christian Dior under John Galliano and at Chanel. I remember asking him, when he was at Dior, what the point was of making couture by hand. Why is everything sewn by hand? I had never really understood that. He replied that everything was in the round — the fabric will do this and that. And there really is a difference. There’s a difference when you see clothes made by hand — and I mean sewn by hand.

And not sewn by hand on a sewing machine…

The clothes do fit the body differently. All of these things are kind of a piece now. I remember talking to Lauren Hutton about [Richard] Avedon and she said it would take several days to do a fashion shoot with him. They’d shoot and, the next day, they’d look at contact sheets from the previous day. They’d find something they didn’t even know about — an oh-that’s-really-good kind of mistake. Instead of someone looking at a monitor while you shot, you had more room for spontaneity and things randomly happening.

I noticed this isn’t your only book this month. There’s Dior: New Couture, featuring Patrick Demarchelier’s photos.

That was fun to do. In my conversations with Raf [Simons, Creative Director at Dior], he said, right from the beginning, that Christian Dior was more modern than people think. And if anyone knows how to define that, it’s Raf because he has an eye for it. And then going back through all the Dior books — and I actually read his autobiography for the first time — I was blown away by how many things are clues to the way he thought. I think the mixing of historicism and what’s happening in the contemporary are what gives clothes their energy. And, obviously, if you read histories of Dior, people were gaga-crazy over Dior in the New Look years; it was revolutionary. In a way, Raf just made it easier to see that Dior was far more modern than people give him credit for. And Galliano, too. I mean, sometimes with John, because it got so over the top, it was very hard to see the connections that Dior was making, but they were there.

And now Galliano’s at Maison Martin Margiela…

There is a common ground between John and Martin. They’re showmen and they know how to interpret clothes. Some of the best shows in Paris in the Nineties were from Martin. I remember the one at the Salvation Army — I sat on a washing machine. Those things, you know, John can be quite clever at and now he’s had some time to think about things and what he’ll want to do. It’s just going to be a question of — again, the industry moves so quickly and the commercial sides of the business are about cranking out lots of clothes. The show almost becomes a separate thing. Today, everyone just accepts that’s the way it is.

What’s next in the pipeline?

I’m doing a book on the history of The New York Times fashion coverage. It’s a lot — from 1852. Some of the stuff in the 1850s, I swear, you need to have a French dictionary next to you to understand it.