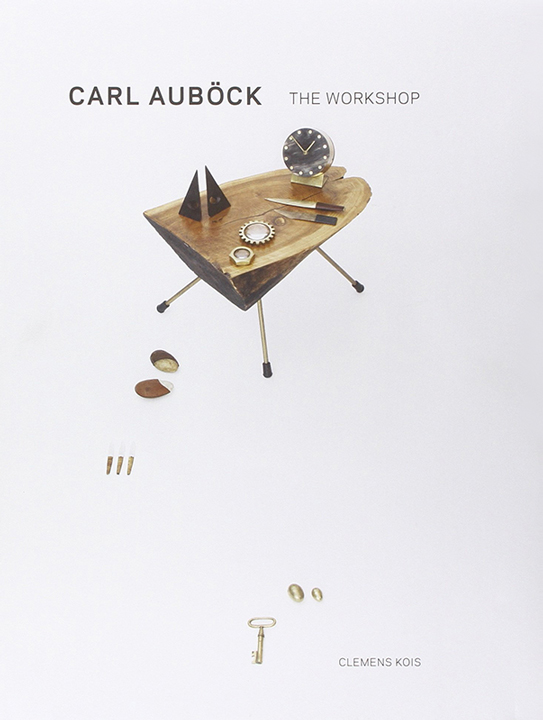

When people discuss the revolutionary work of Carl Auböck — one of the key inspirations behind Tory’s Resort 2016 collection — they’re most likely talking about Carl Auböck II, the Austrian modernist designer famous for his playful brass objets, like sugar-cube holders and hand-shaped cork screws. But there were actually four Carl Auböcks — all designers, starting with his father — and the family workshop still continues today, operating out of an old town house in Vienna. Learn all about this multi-generational design powerhouse in the excerpted interview below between his grandson Carl Auböck IV and Vienna-based writer Thomas Brandstaetter, from the 2012 book Carl Aubock: The Workshop (above).

Thomas Brandstaetter: When did the signature style of your workshop and brand, Werkstätte Carl Auböck, develop?

Carl Auböck IV: In the very beginning, our company manufactured traditional bronzes that captured the spirit typical of 19th-century Vienna. The first Carl Auböck, born Karl Heinrich Auböck, produced formal Vienna bronzes of all sizes with naturalistic animal motifs. The golden eagles atop the two obelisks flanking the entrance to Schönbrunn Palace are attributed to him. Only much later though, starting in the late 1920s when an increasing number of designs by my grandfather, Carl Auböck II, began being produced, did something of a characteristic, signature style begin to emerge.

Beyond that, what distinguished Auböck objects was also the significant quality and complexity of the products created at the Werkstätte from that point on. Whereas the processing of a single material like brass, for example, was more or less easy, the mastery of material combinations like brass with horn, cane, or leather in one object was considerably more difficult and what set our workshop and our brand apart. One trade secret that made the rounds at the Werkstätte was, if you employ a number of materials and combine them with special, key details, imitation by competitors will be rendered virtually impossible.

TB: How did your workshop make the transition from classic Vienna Bronzes to the innovative, yet functional designs now associated with Carl Auböck?

CA IV: Following World War I, most of what we produced was merely decorative to help our employees and the family make ends meet. Only slowly did we accumulate enough resources to buy the materials necessary to create the very first pieces based on our own designs. One example of these early signature objects was a pair of Carl Auböck bookends. Shaped like animals and hand-sketched in our working and ordering catalogues by my grandfather, Carl Auböck II, the illustrations reflect the influence of the Johannes Itten drawing class he had taken, where they practiced symmetrical drawing with both hands. Grandfather was ambidextrous by nature and, therefore, had a very keen sense of spatial understanding and imagination. He created many of his designs during meetings with clients, sometimes sipping Turkish coffee and all the while smoking.

A mix of relaxed small talk and the targeted exchange of technical know-how was customary at the workshop. The tasks at the Werkstätte were clearly defined and structured according to each individual’s talents and specialization. Workers were assigned jobs based on their skills, and their contribution determined their rank. “Busch,” for instance, was perfect at making tree tables, and “Schabel” worked best with “Novak” on the delicate hinges of cigarette boxes. It was like an all-star band – together they strove for quality and, individually, each one possessed this spirit of achieving the highest standard in his own work. The hierarchy was constantly shifting and everybody had the chance to expand on his own realm of expertise. But they were constantly being put to the test in terms of quality.

Our father, Carl Auböck III, had the unique opportunity to learn about materials and their processing from this collective of interesting characters from very early on, as did I later on, in the early 1960s.

TB: What was the driving force behind the work of [your father, Carl Auböck III, and your grandfather, Carl Auböck II]?

CA IV: I would say the search for an object’s underlying purpose was clearly important to both of them. Most of their designs, for example, were created for the living and dining rooms, for the stage of hospitality, so to speak. Household culture, shifting lifestyles, and gift-giving were an essential part of their vision. People gave each other vases, salt shakers, and other table objects as hostess gifts or favors. All these objects could be held in one’s hand and handed to someone. They served a table culture and lifestyle that was communicative. One can discuss these objects time and time again. They have a history, an aura, a purpose, an idea. They are conversation pieces.

TB: Were there any international influences for the Werkstätte Carl Auböck?

CA IV: Grandfather combined his father’s excellent tradition of craftsmanship with innovation and an avant-garde spirit. He met the Bauhaus masters Oskar Schlemmer, Paul Klee, Walter Gropius, and many others during his time in Weimar, in addition to his personal friendships with fellow students Otto Breuer, Franz Probst, and Alfred Lipovec at the Bauhaus who definitely had the greatest impact on him.

My father, on the other hand, did his postgraduate architecture studies at M.I.T. in the early 1950s, together with Henning Larsen. While there, Walter Gropius arranged for them to stay at the home of Charles and Ray Eames for a week. Two years later Eames designed his first case study house in Uniontown, Pennsylvania. Naturally, my father brought the knowledge and inspiration he got from those trips back home with him. Furthermore, a number of international designers like the Japanese-Americans George Nakashima and Isamu Noguchi and the “era of prefabrication” had a great impact on him. For instance, CA III was able to incorporate and expand on his newly-acquired knowledge of American prefabrication techniques in the first housing estate he built together with Roland Rainer, in the Hietzing district of Vienna. That’s the way it was back then. Novelties were imported from abroad. There was no faucet of information like we have today with the internet.

TB: The Bauhaus school never distinguished between the art of craftsmanship and fine art. Is this the stance also taken by Werkstätte Carl Auböck?

CA IV: For me, there is only such a thing as one art. When it appeals to, touches, or even irritates me, then I don’t care which of these art categories it falls into. It’s a question of spirituality and the permeation of culture. It goes without saying that, to some degree, we are always aspiring to create something more than just design, to give the spirit a form, so to speak. With good design, one can always distinguish the spirit in that design. It’s something that goes beyond mere function.