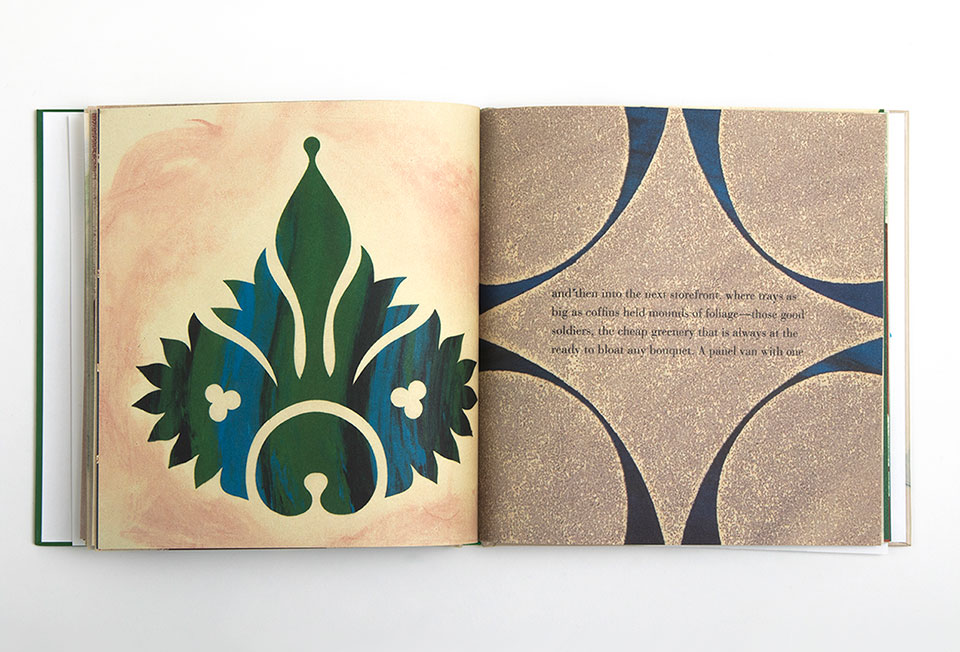

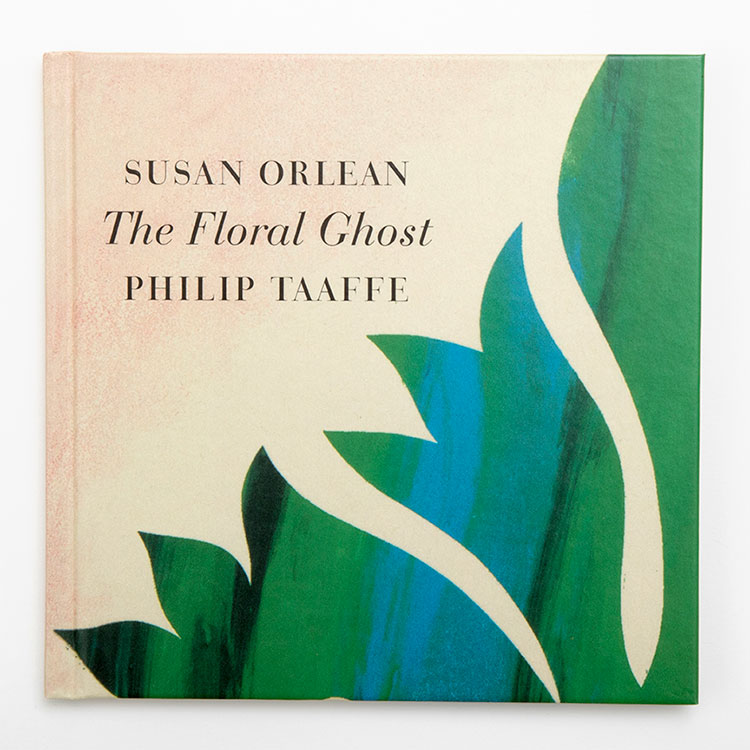

Author Susan Orlean has a way of reframing things you see every day and making them utterly magical with a spirited description or an amusing turn of phrase. She did it with The Orchid Thief, which inspired the 2002 film Adaptation (starring Meryl Streep as Orlean), and she does it with her countless magazine articles in The New Yorker. Her latest book, about New York’s dwindling Flower District, is another case in point. “The first time I ever visited the Flower District was late in the afternoon on a hot day so many years ago that even my memory of it has crisped around the edges,” begins Orlean in The Floral Ghost (Planthouse Gallery), which was done in collaboration with artist Philip Taaffe. It’s a beauty of a read — both her evocative words and his gorgeous floral graphic prints will be imprinted on your mind well after you turn the last page. Here, Orlean talks to us about the work, her New York and the writing process.

A while ago, I was approached by an old friend, Katie Michel, who had a gallery in the Flower District and was getting booted out because the space was getting converted into something fancy — condos or something. She had this idea of doing a group show reflecting on the end of the Flower District and asked me to write an essay to accompany it. I was excited to do it because the Flower District had sentimental connections for me and she had gathered these amazing artists to do the show and [accompanying] portfolio. Then Katie came up with this idea of taking my essay and the work of one of the artists in the show, Philip Taaffe, to create a book that would be something anybody could purchase, as opposed to this very limited-edition portfolio that was thousands of dollars.

The relationship between the artwork and my essay…

The essay was never meant to be a response to the artwork, as much as we were all together meditating on this same theme. I think mine was one of the last pieces that were finished.

The story behind the title The Floral Ghost…

As I recall, they were hanging the show, and when they peeled away some of the paint on the walls to prepare for it, they found the old flower shop had listed the flowers they had, information about the flowers… It was this very ghostly reanimation of what this space had been. It was as if the ghost of the space’s previous life was popping out.

Favorite line in the essay…

That’s like “Which child do you like the most?” I guess it’s at the end of the essay, the idea of the conversation of things: “And here, on this dirty, gummy sidewalk in this clattering city, crates of merchandise would undergo that same sort of conversion; they would be made into something singular and beautiful for someone, and it might last just a moment, as so many singular and beautiful things do, but the image of it, flower and leaf, would last.”

The essay itself…

You know, it was a real joy to do this because sometimes these essays are bedeviling — they can be so hard. I knew we were trying to keep it relatively short, and I wanted it to mean something. It happened to dovetail very nicely with something I often revisit in my work, this sense of evanescence and this passage of time, and the passage of beauty into nothingness… And, of course, since it was so connected to a time of my life in New York, and now I don’t live in New York anymore, it was really very emotional. Rather than just “Oh, my goodness, New York is getting so gentrified,” it was really very much about the passage of time and what that feels like, and also about New York as a place. As I was writing it, I suddenly thought, Wow, everything I am describing is very much what the nature of living in New York is Hoards of people arrive with this dream of inventing themselves and being turned into something distinctive; it was definitely my experience of coming to New York.

My first day in New York and initial impressions…

I spent a lot of time in New York as a visitor before I moved there, but I remember moving and feeling, truly, just baffled by how you did it, how you navigated this massive place. It was so funny for somebody who had spent a lot of time there, had lived in other cities and considered herself, you know, pretty sophisticated. I felt like a farm girl. I felt so naive. New York is such a unique place that it’s possible, maybe like almost nowhere else, for you to feel like a child. It’s hard to arrive there and feel super-confident, like “Oh, I got it. I know how to do this.” Every time you move somewhere, there’s that period of time when you really are stripped back to feeling like you don’t quite know how to make your way. Even though it can be a struggle, it’s like a rebirth. You really are wide-eyed. And New York really did that to me in the most basic way. Like, I couldn’t figure out how you get your groceries. What do you do with your car? Where do you get gas? Things that, in every other city in America, are pretty obvious and in New York they are not. When I think about it, I really just did not know how to get anything done.

I think it was gradual, like boiling a frog. It’s a slow and steady accretion of knowledge and, suddenly, you barely recognize yourself. You think, “Wow, I’m that person who knows how to hail a cab and knows when someone says ‘Eighth and 11th’ what that means.” I don’t think there was a moment when I thought, “Today is the day that I’ve become a New Yorker.” But I do think that, gradually, I reached that point, and I would walk through the city and sometimes felt like I was observing myself from the outside, thinking, “Here I am walking through New York City like I know what I am doing!”

Aside from the Flower District, other New York neighborhoods I love and miss…

The entire time I lived in New York — which was quite a long time — I lived on the Upper West Side. And, of course, to go back there and see all the neighborhood stores replaced by Victoria’s Secret and Bank of America… I have this deep pang. There was a place on the corner of 86th and Broadway called William’s Barbecue. It was an old-style roast-chicken joint, a neighborhood place that had been there forever. I took it hard when it closed because, to me, it was such a sign of the neighborhood. It really broke my heart when I went back on a visit and saw that it was gone and replaced by a bank. I used to feel like I could live in my building and everything I needed was within a two-block radius, and, increasingly, that’s not the case. But more than that, it was the sort of eccentric character of New York, the distinctiveness, the fact that you wouldn’t find a William’s Barbecue in every city across the country.

On change…

I know change is inevitable. New York is a city that churns all of the time, and a lot of the vitality comes from people moving in, moving out, businesses opening and closing. I try not to sentimentalize moments and feel like life should have stopped at that moment. But what I do feel sentimental about is the feeling that what should have replaced William’s Barbecue is something else eccentric in its individuality. I really get into arguments with people who say, “You know, music, when I was a kid, was great, and now it’s awful!” I think, “Well, that’s ridiculous.” I think we have a tendency to have moments in our lives that we want to preserve in amber, and see that moment as good and change from that as a downhill slope. I don’t feel that way. I feel that change is part of what makes life exciting. But what’s unfortunate is when change skews in the direction of ordinariness, of monolithic commercial development, stuff that doesn’t feel special. I do really feel sad about that.

New York as a city of makers versus, increasingly now, a place where things are bought…

A city of “makers” is a really exciting, dynamic place — even in the grittiest part of that “making.” I love factories, I love wholesale stuff, I loved walking through the Fashion District and seeing buttons and ribbons. To me, that was a lot of the nature of New York, which is: This is where it all begins, where the waitress becomes a star and where the button in this shop on 37th Street ends up on a runway in Paris. Now it’s a gigantic commercial portal, a city where you come to purchase. And that doesn’t have nearly as much interest for me; it doesn’t have the energy. Frankly, it doesn’t attract the same variety of people.

Favorite place to write…

Because I have moved a fair amount, I’m somebody who doesn’t need a particular sacred place to write. Although, when I’m working on bigger projects when I have tons of material, I like to work somewhere where I have my stuff spread out around me. I guess I like to write in a place that’s fairly cocoon-like and rather plain. When I was at The New Yorker, I had an office with a spectacular view and I traded offices with someone because I found the view sort of distracting. He had an interior office with no window, and I really liked it more. I like to curate the space, put things around me that I like, but I don’t like to have a lot of stuff. I don’t play music while I’m writing. It’s a fairly peaceful environment.

I’m generally pretty adaptable. It used to be that my sweet spot for writing was midday to evening — and then I had a child! Suddenly, that was not working, so I’ve had to change my schedule accordingly. When the school day ends, my productivity plummets. I’ve had to shift to working earlier.

My secret to combating writer’s block…

I’ve always believed that writer’s block isn’t a matter of not knowing how to say what you want to say, it’s that you don’t yet actually know what you’re trying to say. So when I’m really stuck, I see it as a signal that either I haven’t done enough reporting — if I’m doing something that’s heavily fact-based — or, in the case of an essay like this one, I haven’t really thought it through enough. Walk away and just let it sink in a little bit more. Think through what it is you are trying to say. Don’t sit there and keep banging away fruitlessly at the keyboard. And because I’m partly superstitious, I never like to identify any period of being stuck as writer’s block because I think it’s bad to put a name on it. It’s like, “No, it’s not writer’s block! I’m just going slowly!”

On my Skyping into book-club meetings…

I’ve enjoyed it. I feel like I learn something from people’s questions. If you’re a writer, a huge part of what you are trying to do is to communicate. It’s particularly relevant to hear people’s questions because I think it helps you understand what you’ve communicated or, sometimes, what you failed to communicate. I haven’t done a book club in a while, but I Skyped into one after [my book] Rin Tin Tin came out and I ended up becoming very good friends with one of the women I got to know via the Skyped book club.

On the subjects I cover, which range from Rin Tin Tin to The Orchid Thief…

I almost never return to the same subject. I’ve been asked many times to write about orchids again. I have almost not a phobia but a real resistance to revisiting anything I’ve written about. Not because I’m not still interested but because usually I feel like I’ve done it. This is, of course, the incredible irony of The Orchid Thief — writing about a guy who I felt abandoned interests and passions in a way that I found so weird and then realizing, with a real shock, that that was very much what I do. It’s the nature of my work: I fall madly in love with the subject, I want to learn everything about it and then, when I’m done, I really move on, and I move on very definitely.

For me, writing is…

My way of understanding the world and my place in it.

Next up…

I have an essay in William Wegman’s new book and in One: Sons & Daughters, by Edward Mapplethorpe. But mostly I’m working on my new book, which is about the Los Angeles Public Library. I’m just starting to write that…