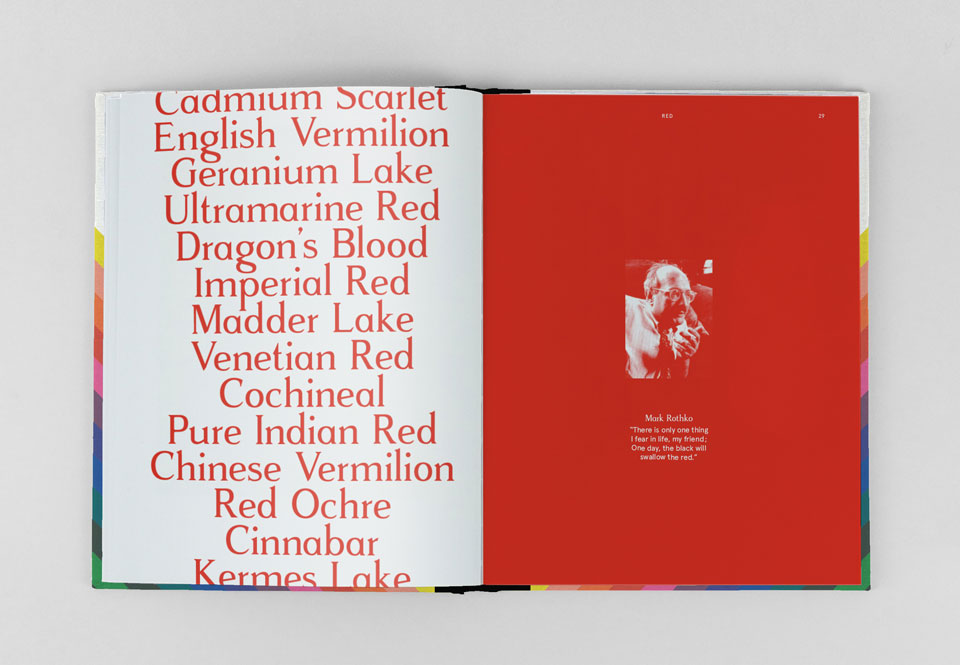

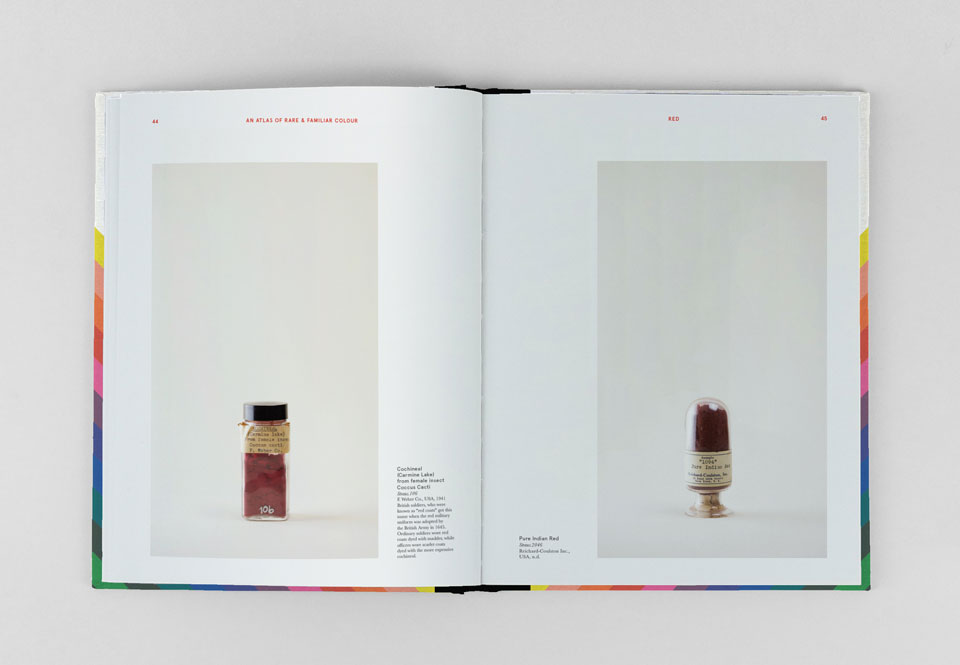

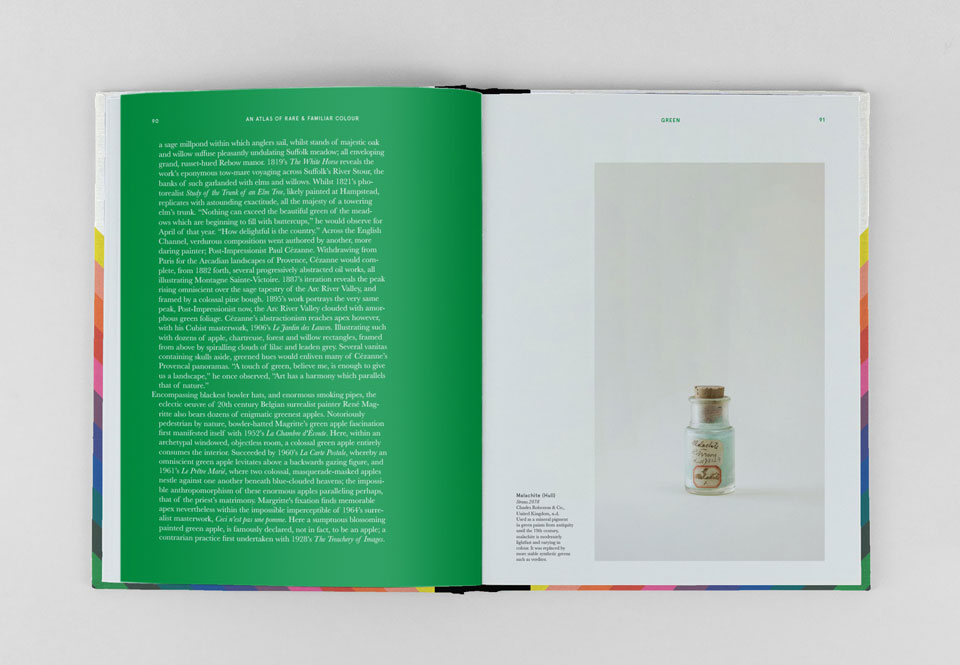

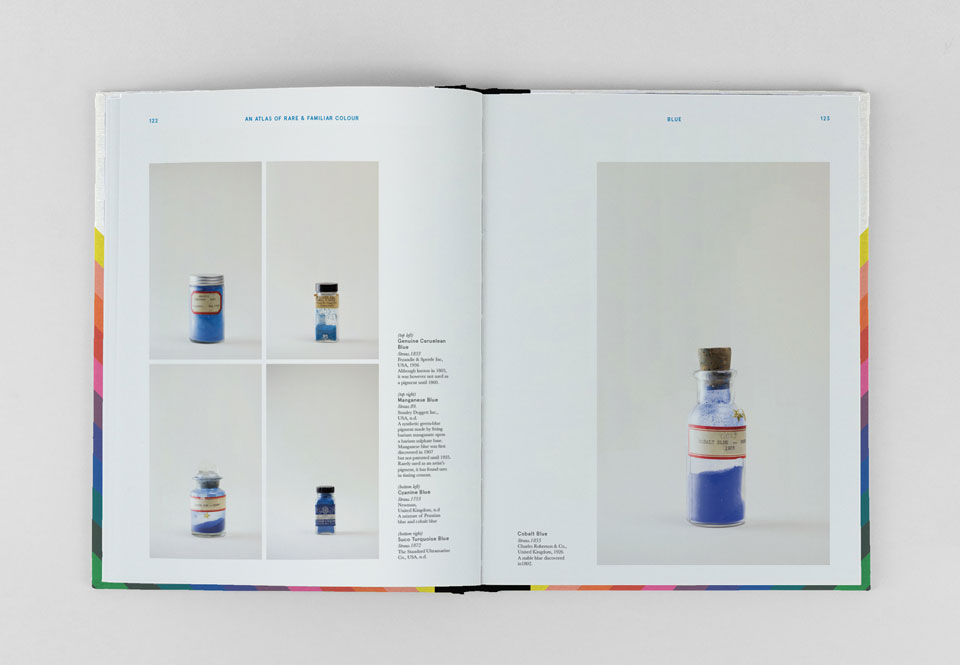

The premise is simple enough. The book catalogues the Forbes Pigment Collection, located at The Harvard Art Museums. There are over 2,500 pigments in the archives; An Atlas of Rare & Familiar Colour features the highlights in meticulous detail, like specimens in a lab, with images of the colors in vials and test tubes. The result isn’t quite that dry. The accompanying text by Dr. Narayan Khandekar and Victoria Finlay, who wrote the forward, is as enjoyable as it is informative. There’s the technical stuff, yes — color theories, the impact of light and all that — but also engaging cultural and historical storytelling.

Did you know, for instance, that there’s a shade of brown — used by painters such as Eugene Delacroix — called mummy brown? The pigment actually includes crushed remains from real Egyptian mummies. Finlay tells the story of a young Rudyard Kipling watching his uncle, artist Edward Burne-Jones, materialize from his studio, “shocked to have learned that Mummy Brown was in fact ‘made of dead Pharaohs.’ So he organized a funeral procession for his paint tubes, and they buried them beneath a tree in the garden.”

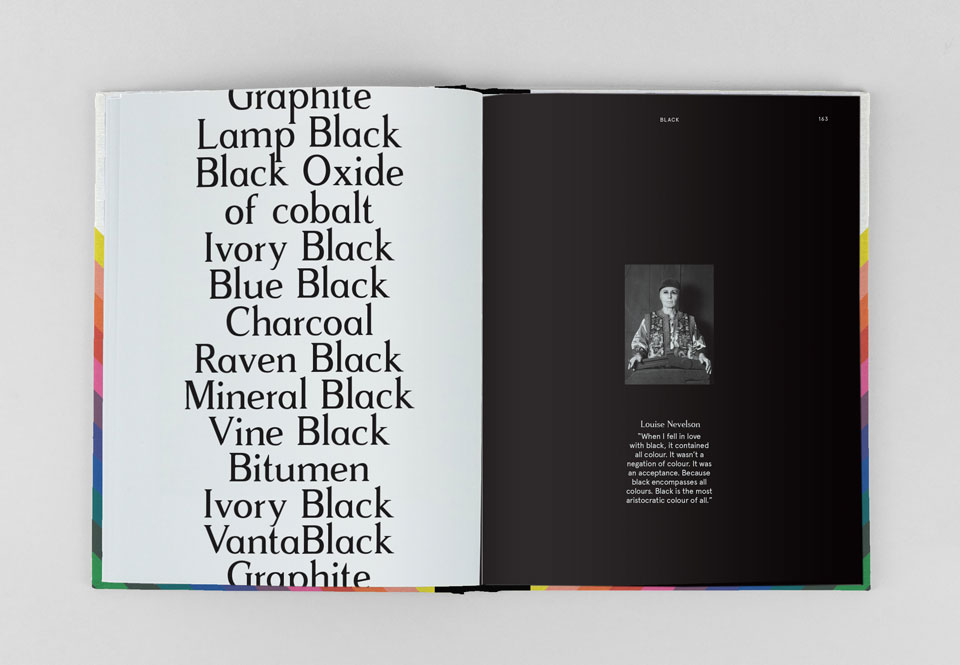

An Atlas of Rare & Familiar Colour covers the more modern pigments, too. YInMn Blue, accidentally discovered in a university lab in 2009, is in there. So are pigments by Mark Rothko, Jackson Pollock and Roy Lichtenstein. The newest entry is 2016’s Vantablack, the only black to absorb every visible wavelength. The blackest of blacks, it’s like staring into “visual deprivation,” Finley writes. Sculptor Anish Kapoor has an exclusive license to use Vantablack in art, “which has caused some controversy,” she continues, “leading artist Stuart Semple to produce the ‘pinkest pink’, which is available to all except Kapoor. Naturally, we hastened to acquire a sample of Semple’s Pinkest Pink.”