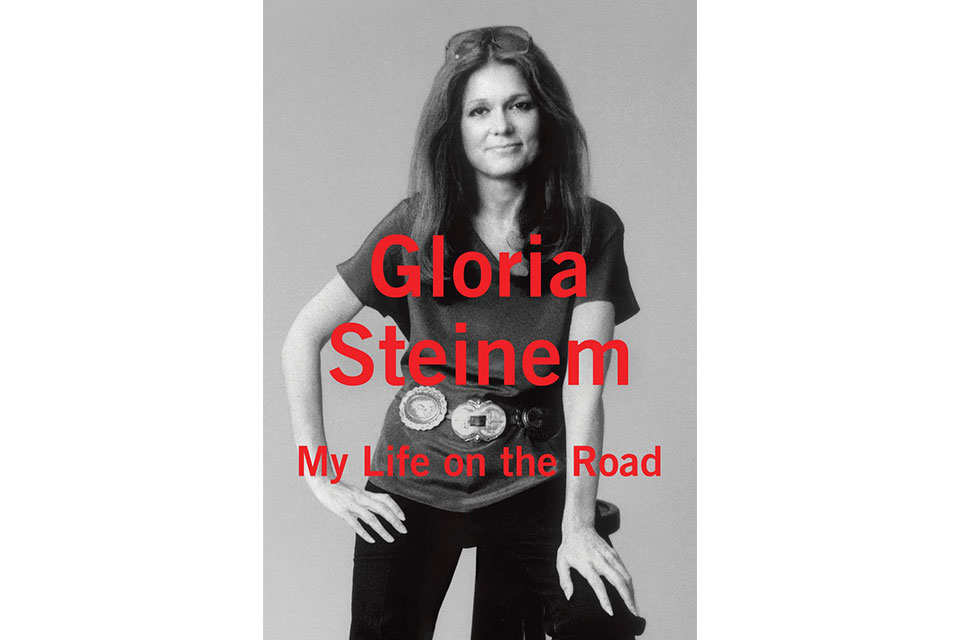

Gloria Steinem — no introduction necessary. Those two words, that name, is enough to evoke whole movements, eras, social and political changes… In her new book My Life on the Road (Random House), the feminist force takes the reader on quite a trip, both figuratively and literally. Hers was a life led on the road — and Steinem traces through it in intimate detail, from university campuses across the U.S. to “talking circles” in India, from coffee shops to truck stops, from Martin Luther King Jr.’s speech at the Lincoln Memorial to a biker gathering in South Dakota. Her nomadic nature, she explains, comes courtesy of her father, a traveling antiques dealer; her mother, meanwhile, instilled in her a love of community because, Steinem writes, she saw “the price my mother paid for having none.”

Here, a few excerpts from My Life on the Road.

“Since my parents believed that travel was an education in itself, I didn’t go to school. My teenage sister enrolled in whatever high school was near our destination, but I was young enough to get away with only my love of comic books, horse stories and Louisa May Alcott. Reading in the car was so much my personal journey that when my mother urged me to put down my book and look out the window, I would protest, ‘But I just looked an hour ago!’ Indeed, it was road signs that taught me to read in the first place — perfect primers, when you think about it. COFFEE came with a steaming cup, HOT DOG and HAMBURGERS had illustrations, a bed symbolized HOTEL, and graphics warned of BRIDGE or ROAD WORK. There was also the magic of rhyming. A shaving cream company had placed small signs at intervals along the highway, and it was anticipating the rhyme that kept me reading:

“If you

don’t know

whose signs

these are

you can’t have

driven

very far.

Burma Shave”

On August 28, 1963, at the Lincoln Memorial

“Martin Lurther King, Jr., read his much-anticipated speech in a deep and familiar voice. I’d always imagined that if I were present at the creation of history, I would know it only long afterward, yet this was history in the moment.

“As King ended his speech, I heard Mahalia Jackson call out, ‘Tell them about the dream, Martin!’ And he did begin the ‘I have a dream’ litany from memory, with the crowd calling out to him after each image — Tell it! What would be most remembered had been least planned.

“I hoped Mrs. Greene heard a woman speak up — and make all the difference.”

“I was once as obsessed as anybody else with driving as a symbol of independence. I signed up for a driver’s ed course in my senior year of high school, though I had no car or access to one. I wasn’t looking so much to be a driver as to symbolize the difference between my mother’s life and mine. She was a passive passenger, so a driver’s license would begin my escape. In the words of so many daughters who don’t yet know that a female fate is not a personal fate, I told myself: I’m not going to be anything like my mother. When I was in college and read Virginia Woolf’s revolutionary demand for ‘a room of one’s own,’ I silently added, and a car.

“But by the time I came home from India, communal travel had come to seem natural to me. I had learned that being isolated in a car was not always or even usually the most rewarding way to travel: I would miss talking to fellow travelers and looking out the window. How could I enjoy getting there when I couldn’t pay attention? …

“Now when I’m asked with condescension why I don’t drive — and I am still asked — I just say: Because adventure starts the moment I leave my door.”

On Advice in the Friendly Skies

“I’m sitting next to a very old and elegant woman on a plane from Dallas to New York. Assuming that she needs company, I start a conversation. She turns out to be a ninety-eight-year-old former Ziegfeld girl who is on her way to dance in an AIDS benefit on Broadway with her hundred-and-one-year-old friend from chorus girl days — something they’ve been doing since the tragedy of AIDS first appeared. Humbled by this response and looking for advice on my own future now that I’m past seventy, I ask her how she has remained herself all these years. She looks at me as if at a slow pupil. ‘You’re always the same person you were when you were born,’ she says impatiently. ‘You just keep finding new ways to express it.’”